Dear Tamar:

I would love to be a lettuce-fiend, but I am not: I make too much salad. And it’s either too exciting (as in: overwhelming) or not exciting enough. Now, the CSA basket holds barely anything but lettuce (4 heads this week!) and radishes—and there seems to be only salad to be made. A pesky wisdom-tooth issue has gotten even more in the way of lettuce-enjoyment—I can’t properly chew. Is there anything to be done? Can it be cooked to make it more easily chewable (and make it keep longer)? Or does one have to accept that it’s inherently vergänglich? Thank you so much for your help.

-Involuntarily Wilting

Dear Involuntarily Wilting,

In 2008, I had a nervous breakdown. (It may have been 2007 or 2009.) The adjective “nervous” seems quaint, almost Victorian. What happened wasn’t quaint. It was fragmented and overpowering. In the midst of it, I was introduced to a journalist named Naomi Starkman. I arrived at our introduction quaking. She asked if I could picture myself suspended, high over water, one foot on each of two planks of wood, trying to balance—trying not to fall, keeping each foot on its own plank. I nodded. “Life is like that,” she said. “It’s always like that. You’re always on two planks.”

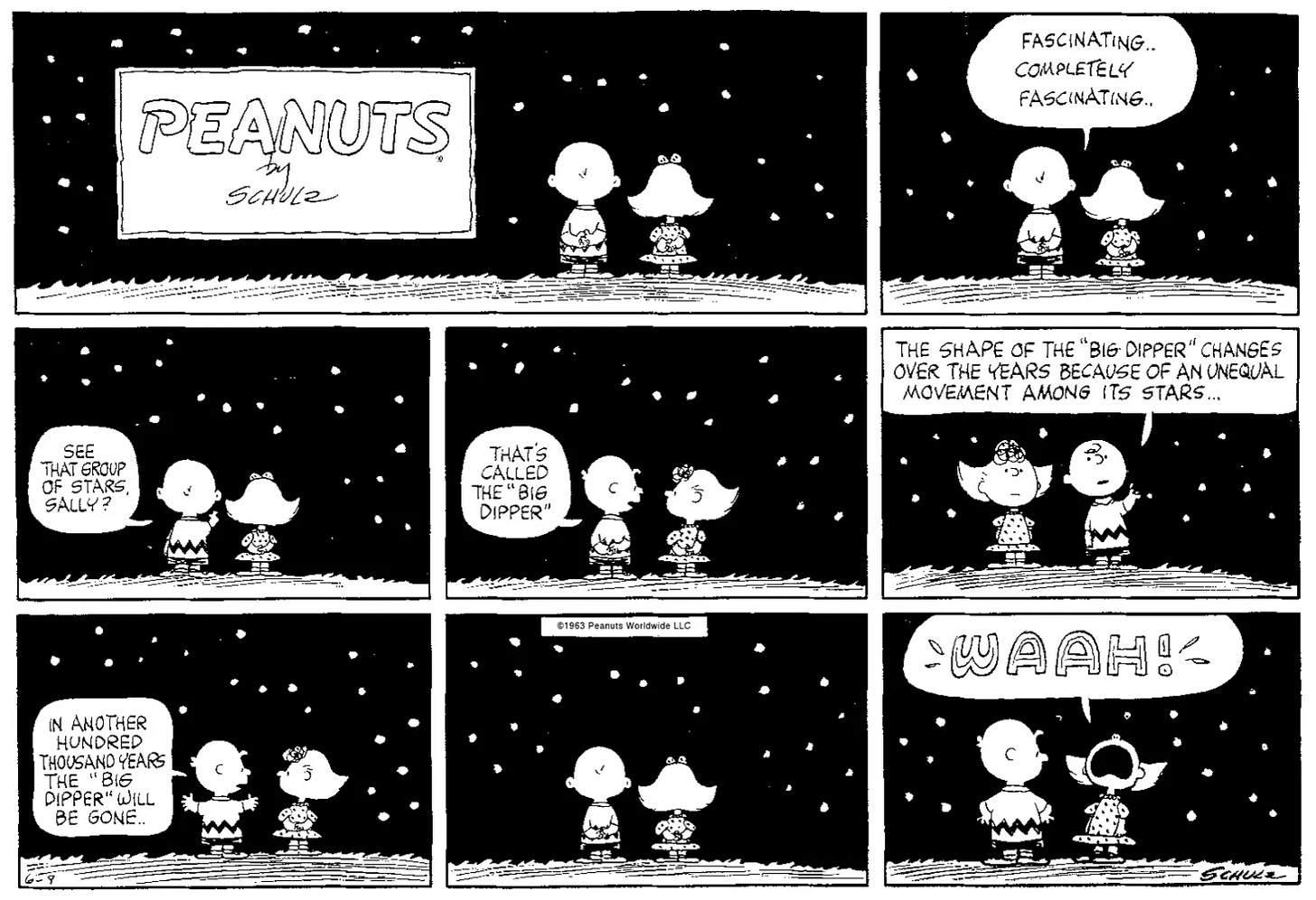

Because I was in extremis, I was able to understand that even the most solid-seeming things are, in fact, suspended among planks. The planks, of course, go by different names. For our purposes today, we’ll call them “vergänglich” and “unvergänglich,” or “fleeting” and “permanent,” or “fugacious” and “everlasting,” to match the pacing of the German.

Why have I spiraled so deep? Because since I learned about the planks, I’ve seen that nothing I can think of, or touch, or see, or invent is any more fugacious or everlasting than anything else. Lettuce is as good an example as any. Lettuce is called lettuce from Lactuca sativa L—the milk-giving cultivar—owing to the milky white substance it leaks when you cut it. The most fragile, fleeting food, given a Latin name for the universal symbol of new life. It’s almost too on the nose.

The suspension of existence between states is essential to understand because to cook well—as to live well—you must dig into each state. To eat lettuce raw, embrace what makes it uniquely fleeting—its crispness, its wateriness, its delicacy, its refreshingness. For a lettuce salad that won’t be too much or too little, use only lettuce—or at most, lettuce and radishes. Dress the leaves in a way that makes lettuce more lettuce-y: make a dressing of fresh green garlic (also fleeting)—finely chopped and pounded to a paste with salt—lemon juice, a tiny smidge of smooth Dijon mustard, whole milk yogurt or heavy cream, a little water, and, if your yogurt is thin, a little olive oil. If you have tarragon or dill, chop either and mix it in. Even a non-fiendish lettuce eater will enjoy garlicky, creamy dressing on crisp lettuce.

And now, hot-water-bottle held to your aching tooth, dig into the other plank. Lettuce is wonderful cooked. It can be cooked just like other leafy greens and used to be, quite often. It still is in some cuisines. Lettuce was yesteryear’s kale or Brussels sprouts. I love cooked lettuce—so much that in one quick search, I found four past instances of my own writing about it rapturously.

First I came across this recipe for Rice and Lettuce soup, from my first book. It’s soothing and requires a good deal of lettuce. It would provide great comfort from a painful wisdom tooth. A friend called “butter’s highest and best use, because the lettuce becomes an expression of butter.”

I once wrote an entire magazine column poeticizing cooked lettuce, with written instructions for a creamy, blended lettuce soup, even easier on aching dentistry. Here it is:

I know only three or four good [lettuce soup recipes]. The first is soup à la Dauphine, from Alexandre Dumas père, which calls for wilting lettuce, spinach, leek, onions, sorrel, purslane and edible flowers in butter, adding vegetable stock and serving over toast…I wilt onions in butter, then add whatever soft herbs, like parsley, chervil, savory, tarragon, mint, I have—the more the merrier—then lettuce leaves and barely enough water to cover them. I cook it just as long as it takes to really get hot, then purée it, with a little more butter or a drizzle of good olive oil. The whole operation is quick, and the result is simple and good, and even better the next day.

The same column provided this recipe for braised lettuce on anchovy toast, which I make semi-religiously. The result tastes nothing like lettuce, or anchovy, or even really like toast, but like a combination that predated any, which I stumbled upon in a lucky mood. My recipe calls for too much salt. I use less than I advised in the column. (Mea culpa.)

The next one is even more rapturous.

For years I have cooked petits pois a la francaise, a classic French preparation of green peas and lettuce, under the impression that I was following a classic recipe I’d read in How to Cook a Wolf…But I find myself rebuked, having been tricked by my own memory—like most of its species in a constant state of half-eclipse. My petits pois a la francaise, which I think an ideal combination of sweet butter, wilted lettuce, fresh peas, and bacon lardons, is not M.F.K. Fischer’s…nor even Ali-Bab’s. Ali-Bab’s doesn’t even contain lettuce…After wondering if I’d dreamed my version up entirely, I was informed not overly gently that this my brother’s recipe, almost exactly.

Your lettuce seems in a state of near escape because it is. But so is everything else. My newest book has a slew of cooked lettuce recipes, for lettuce that’s old, or leftover, or already dressed. Even lettuce that is hanging by its nails from the fugacious plank can be made everlasting, if allotted the butter and salt and heat endurance demands.

Dear cook, acknowledge that your lettuce is both ephemeral and durable. Treat it lightly, or treat it firmly; be minimal, or buffet it with butter and demand its surrender in a Vitamix. Try hard, then let it go, and go along with it. Can it be both there and gone? Can it be anything but?

This had me thinking about how my father loved "old" wilted salad. We laughed as kids and no one else would touch it. Being a frugal sort I have on occasion saved leftover salad and enjoyed it in its altered state. Mutable, more mature, less fussy, and open to new things...is it part of aging?

I love this