Dear Tamar:

I am a relative newcomer to a small city. With two little kids, our best bet for socializing is often around our dinner table. I love hosting and feeding people and I live for a good sobremesa. And yet there are a few acquaintances I'm eager to spend more time with whom I can't work up the courage to invite over. They are *food people* who run their own restaurants and import their own wine. I am just a Cancer with an aspirational cookbook collection. How to get over myself and just do it? What to make them?!

-No Big Meal

Dear No Big Meal,

When I was 28, a Piedmont (Italy) business-and-tourism bureau sponsored a bus tour to expose a small group of visiting American chefs to the region’s delicacies—Carnaroli rice, Robiola, Barolo, truffles, etc.—in the hopes that we’d serve them at our restaurants back home.

A group of hedonistic, masochistic food professionals would file onto a bus after breakfast. By 9 am, we’d be a bottle of Barbaresco in. By 10 we’d each have eaten enough raw beef and Taleggio to feed a medium-sized family. Noon would mark the start of a procession of risottos and fresh pastas at damask and crystal-laid tables at centuries-old rice farms. We were gouty and shiny and drunk. And that was just the first day.

My other memories are mostly impressions. I recall listening to a long speech in Italian in the remnants of a stone building on a small piazza while drinking wine. I remember learning to make agnolotti dal plin—which we all did successfully (we were chefs)—but were too drunk to really remember. (We were chefs.) Thick steaks. Comparing calluses on our hands. It was all too much, amplified—too much for people who are temperamentally too much.

Cal Peternell, however, then chef of Chez Panisse Cafe, was the only other chef who seemed to grasp the ridiculous too-muchness of it all. At least, the only other chef who would sometimes skip the day’s fifth or fifteenth winery to sit in the sun outside the bus and drink espresso with me. Cal and I became fast friends. We learned to catch each other’s eyes during long-winded welcome speeches in Italian, raising glasses of Barolo to each other.

Several months later, I went to cook at Chez Panisse. So it happened that I ended up friends with my boss—who was himself friends with chefs of the other Bay Area restaurants. It didn’t occur to me to be intimidated by all the prestige until my brother, then a cook at Per Se, flew to visit me and arrived to news that we’d be hosting a dinner for a group of well-known chefs. I’d done no shopping or preparing, thinking that we would make polenta, braise pork I’d been squirreling away, cook kale from the garden.

My brother was irate. He spent the afternoon ignoring me while pickling green tomatoes, fussing over them. My polenta and pork were good enough. My brother’s babied green tomatoes were great. The meal was fun, mostly. But seeing all the chefs through my brother’s eyes had destroyed my innocence. I became nervous. I began to panic, to mess up, whenever I cooked for them. (See: This earlier Kitchen Shrink column.) Cal et al. went from being just people to chefs, and try as I might, I couldn’t nudge them back into the old, comfortable category.

This was almost twenty years ago. I’ve been careful, ever since, to keep all chefs I befriend firmly in the category of “people.” I’ve concentrated not on their skills as cooks or hosts, but on how nice it must be to not plan a meal, or lift a knife, choose the wine, worry if there’s enough food, worry if anyone likes their dinner, keep things moving along, clear up, do dishes, be in charge.

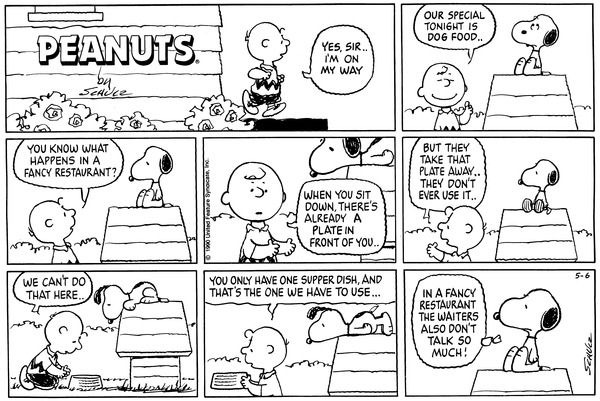

So I invite them. And when I begin to worry that Shaina from Cafe Mutton won’t like my mushrooms, or that Brent from the Meat Hook will think I under-rested his steak, I blame my brother, then remind myself that what *food people* care about is *food* unencumbered by stress. They care about being at a table without anguish. Providing that is my only duty.

Dear cook, invite cooks—and wine importers and butchers—to your table. Of all people, they appreciate most what can happen around one. Don’t cook to impress. Don’t cook to surprise. Don’t cook to experiment, unless your easiest-going self emerges only when pressed through the gauntlet of experimentation. Serve whatever makes you pleased and proud, whether it’s scrambled eggs or Caesar salad or your mom’s lasagna with no-cook noodles. Relieve your guests of anguish by not experiencing it yourself. Who cares if they’re late? Who cares if the eggs are cold? If the croutons sog? If the no-cook noodles still won’t cook. Give *food people* time at the table absent stress and pain. It’s the greatest luxury you can offer. It will serve as a foundation for friendship and community as long as you serve what you make proudly, and invite those who can appreciate the gesture to share it.

I'm so interested in siblings that go into the same profession. For years of my life, I didn't try to write professionally because I thought that was my brother's thing. Now we're both writing and it's great. Turns out there's room for both of us in "writing," which, of course, means different things for each of us because it turns out we are different people. You seem to have avoided the problem I had, but this is a great example of how those sibling relationships get under our skin.

I feel this with every fiber of my being, from my own personal experiences.

Although not a chef currently, I am professionally trained and a skilled home cook and I have never been invited to dinner by anyone. On one occasion I was invited to lunch by a friend who'd just returned from a trip to Italy and brought back amazing pasta which she wanted to share with someone who, as she said, "knows how to appreciate quality food." Friends have told me to my face that they aren't comfortable having me to dinner because they can't cook like I can and lament that I won't like their food. Really, all I want is to sit down at someone's table and share a meal together. I don't care what it is, how it's procured, what store they shopped at, or any details. I just want to share a meal with people I like. Even when I go to a potluck gathering I am faced with people apologizing for not bringing anything extravagant. If they could only see the simple meals I make for my husband and I, the pots of beans and fragrant rice, plates of roasted vegetables drizzled in a tasty sauce, a simple baked potato topped with sautéed mushrooms and steamed broccoli. My food isn't fancy. I just want to share a meal.